installation for piano and vibrating exciters

duration: undefined

production Edison Studio

“What does a piano do without a pianist?

Does it wait, meditate, evoke, or is it simply there?

Does it feel nostalgia for the human?

Perhaps the absence of a human is simply the nostalgia that it feels for itself…

for the sound, the timbre, and the tone.”

(from Bianco Nero Piano Forte)

Installations of “Aura in Visibile.2”

as part of Bianco Nero Piano Forte

Jun 15 – Jul 18, 2009 – Ravenna, Ravenna Festival, Sala dantesca della Biblioteca Classense

Sep 29, 2010 – Jan 13, 2011 – Roma, Entrance of the headquarters of the RAIradio, via Asiago 3

May 17-26, 2019 – Milan, Palazzo Reale, Sala delle otto colonne (also included in Pianocity, Milan)

as independent installation

Sep 24 – Oct 3, 2011 – Venezia, Biennale Musica, entrance of headquarters of the Biennale, Ca’ Giustinian

Oct 06 2019 – Latina, “o. Respighi” National Conservatory of Music, “Le Forme del Suono” Festival

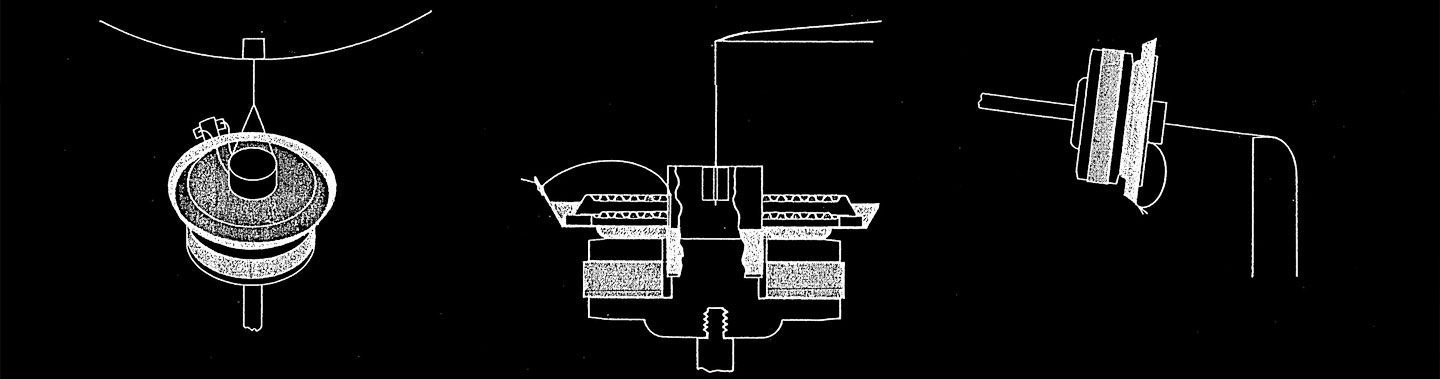

The pianoforte considered as a protagonist in this way seems to observe us, rather than being observed by us. Implacable, black, shiny, tense, and also concretely present, lying on its side, bare, letting its strings sing, stimulated by light electromechanical vibrations”. The new installation of Luigi Ceccarelli, Aura in Visibile.2 is part of a project involving a series of works, entitled Bianco Nero Piano Forte (White Black Piano Forte), realized with the writer Mara Cantoni and the photographers Roberto Masotti and Silvia Lelli. It puts a grand piano – strictly without a pianist – in the centre of the space and of the reflection, and stimulates it by means of mechanical exciters designed by the composer and controlled via a computer, which reveal a totally new voice of the instrument.

Ceccarelli sees the pianoforte as a perfect machine, but one that was fabricated to satisfy the compositional requirements of the 18th and early 20th centuries, when it was necessary to explore harmonic and melodic relationships between sounds. By putting it at the center of a space, solitary, resting on its side and with the cover closed over the keyboard, Ceccarelli invalidates its traditional function

and makes it a “machine that is turned-off” – as he himself describes it – only to reinvent it. He declares that: “The most perfect mechanical contraption constructed for making music is a set of strings stretched upon a frame and ready to vibrate at the slightest touch of the hammers. The piano placed in the Portego exhibition space of the Ca’ Giustinian building, once again the headquarters of the Venice Biennale, creates a sound environment in which live music will be generated, not in the traditional way, but by a sequence of sinusoidal vibrations that pass from the computer to the mechanical vibrators and from these to the strings of the piano and the fusion

of wood and metal that the soundboard transforms into a rich sound. And the keyboard is a sophisticated mechanical interface that transmits the most subtle gradations of pressure by the fingers onto the strings. The scientific theory apparently leaves no room for doubt: the more complex a machine is, and the more faultlessly it carries out its task, the harder it is to adapt it to new developments and changes, and so it inevitably gets old and obsolete. But it is not really so. The limitation is not in the machine, but in the minds of those who use it. At most, it is not in the piano itself, but in the concept of the keyboard as a rigid

regulator of the timbre that limits the sound to strict melodies and equal-tempered harmonies: a sterile barrier that prevents any physical contact between the gesture and the sound. Pianists always played a box without knowing anything of its contents, but in our day music has liberated the piano from its limitations and musicians have discovered that direct physical contact with the strings opens up a new world of sounds, fascinating and very different from those of the past. In order to reinvent itself the piano has had to repudiate the keyboard which had made it so successful in the classical and romantic period.

Luigi Ceccarelli

Reviews

A lot of strange things happen at the 55th Music Biennale. In the pathetic throng of tedious and pedestrian works one certainly has to know where to look. But if one is lucky one comes across a sound continuum with uninterrupted molecular variations, such that two strings are stimulated by the vibrating exciters of technological devices. They resonate sympathetically, and this sympathy is expanded by other strings that also respond and participate, although they are not directly connected. These are the strings of a piano lying on its side in the entrance foyer of the Ca’ Giustinian, an open belly and nothing else. The man who thought of stimulating these strings is Luigi Ceccarelli, a composer of great refinement and inventiveness.

The work is called Aura in Visibile.2 (In visible Aura. 2) and the pleasing thing about it is that at times the continuous flow, a little rough but with a touch of melancholy sweetness, is assailed by short bursts of strong vibration that are modulated in turn, to create a sort of melodic itinerary. Then the sound (in fact there are many unified sounds) becomes darkly soft and “clean”, with an absolutely deep and low sound, but there is always an aura of yearning, along with an intense/painful projection onto the indoor/outdoor spaces. This is a great piece that certainly falls into the category of electronic and artificial music, even though all you can see is an old piano that is playing all by itself.

Mario Gamba – Il Manifesto – 30 September 2011